What is Ulcerative Colitis?

What is Ulcerative Colitis

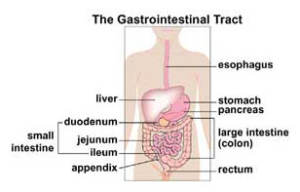

Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of unknown cause. It is characterized by chronic inflammation and ulceration of the lining of the major portion of the large intestine (colon). In most affected individuals, the lowest region of the large intestine, known as the rectum, is initially affected. As the disease progresses, some or all of the colon may become involved. Although associated symptoms and findings usually become apparent during adolescence or young adulthood, some individuals may experience an initial episode between age 50 to 70. In other cases, symptom onset may occur as early as the first year of life.

Ulcerative colitis is usually a chronic disease with repeated episodes of symptoms and remission (relapsing-remitting). However, some affected individuals may have few episodes, whereas others may have severe, continuous symptoms. During an episode, affected individuals may experience attacks of watery diarrhea that may contain pus, blood, and/or mucus; abdominal pain; fever and chills; weight loss; and/or other symptoms and findings. In severe cases, individuals may be at risk for certain serious complications. For example, severe inflammation and ulceration may result in thinning of the wall of the colon, causing tearing (perforation) of the colon and potentially life-threatening complications. In addition, in some cases, individuals with the disorder may eventually develop more generalized (systemic) symptoms, such as certain inflammatory skin or eye conditions; inflammation, pain, and swelling of certain joints (arthritis); chronic inflammation of the liver (chronic active hepatitis); and/or other findings.

Causes of Ulcerative Colitis

Although considerable progress has been made in IBD research, investigators do not yet know what causes this disease. Studies indicate that the inflammation in IBD involves a complex interaction of factors: the genes the persont has inherited, the immune system, and something in the environment. Foreign substances (antigens) in the environment may be the direct cause of the inflammation, or they may stimulate the body’s defenses to produce an inflammation that continues without control. Researchers believe that once the IBD patient’s immune system is “turned on,” it does not know how to properly “turn off” at the right time. As a result, inflammation damages the intestine and causes the symptoms of IBD. That is why the main goal of medical therapy is to help patients regulate their immune system better.

Symptons of Ulcerative Colitis

The first symptom of ulcerative colitis is a progressive loosening of the stool. Gastrointestinal TractThe stool is generally bloody and may be associated with  crampy abdominal pain and severe urgency to have a bowel movement. The diarrhea may begin slowly or quite suddenly. Loss of appetite and subsequent weight loss are common, as is fatigue. In cases of severe bleeding, anemia may also occur. In addition, there may be skin lesions, joint pain, eye inflammation, and liver disorders. Children with ulcerative colitis may fail to develop or grow properly.

crampy abdominal pain and severe urgency to have a bowel movement. The diarrhea may begin slowly or quite suddenly. Loss of appetite and subsequent weight loss are common, as is fatigue. In cases of severe bleeding, anemia may also occur. In addition, there may be skin lesions, joint pain, eye inflammation, and liver disorders. Children with ulcerative colitis may fail to develop or grow properly.

Approximately half of all patients with ulcerative colitis have relatively mild symptoms. However, others may suffer from severe abdominal cramping, bloody diarrhea, nausea, and fever. The symptoms of ulcerative colitis do tend to come and go, with fairly long periods in between flare-ups in which patients may experience no distress at all. These periods of remission can span months or even years, although symptoms do eventually return. The unpredictable course of ulcerative colitis may make it difficult for physicians to evaluate whether a particular course of treatment has been effective or not.

Types of Ulcerative Colitis and Their Associated Symptoms

The symptoms of ulcerative colitis, as well as possible complications, will vary depending on the extent of inflammation in the rectum and the colon. Because of this, it is very important for you to know which part of your intestine the disease affects.

One common subcategory of ulcerative colitis is ulcerative proctitis. For approximately 30% of all patients with ulcerative colitis, the illness begins as ulcerative proctitis. In this form of the disease, bowel inflammation is limited to the rectum. Because of its limited extent (usually less than the six inches of the rectum), ulcerative proctitis tends to be a milder form of ulcerative colitis. It is associated with fewer complications and offers a better outlook than more widespread disease.

In addition to ulcerative proctitis, there are several other types of ulcerative colitis. The following is a description of each type, together with some commonly associated symptoms and potential intestinal complications:

- Left-sided colitis: Continuous inflammation that begins at the rectum and extends as far as the splenic flexure (a bend in the colon, near the spleen). Symptoms include loss of appetite, weight loss, diarrhea, severe pain on the left side of the abdomen, and bleeding.

- Proctosigmoiditis: Colitis affecting the rectum and the sigmoid colon (the lower segment of colon located right above the rectum). Symptoms include bloody diarrhea, cramps, and tenesmus. Moderate pain on the lower left side of the abdomen may occur in active disease.

- Pan-ulcerative (total) colitis : Affects the entire colon. Symptoms include diarrhea, severe abdominal pain, cramps, and extensive weight loss. Potentially serious complications include massive bleeding and acute dilation of the colon (toxic megacolon), which may lead to perforation (an opening in the bowel wall). Serious complications may require surgery.

Diagnosis of Ulcerative Colitis

Physicians make the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis based on the patient’s clinical history, a physical examination, and a series of tests. The first goal of these tests is to differentiate ulcerative colitis from infectious causes of diarrhea. Accordingly, stool specimens are obtained and analyzed to eliminate the possibility of bacterial, viral, or parasitic causes of diarrhea. Blood tests can check for signs of infection as well as for anemia, which may indicate bleeding in the colon or rectum. Following this, the patient generally undergoes an evaluation of the colon, using one of two tests — a sigmoidoscopy or total colonoscopy.

To perform a sigmoidoscopy, the doctor passes a flexible instrument into the rectum and lower colon. This test allows the doctor to visualize the extent and degree of inflammation in these areas. A total colonoscopy is a similar exam, but it visualizes the entire colon. Using these techniques, your physician can detect inflammation, bleeding, or ulcers on the colon wall, as well as determine the extent of disease. During these procedures, the doctor may take samples of the colon lining, called biopsies, and send these to a pathologist for further study. Ulcerative colitis can thus be distinguished from other diseases of the colon that cause rectal bleeding — including Crohn’s disease of the colon, diverticular disease, and cancer.

Another diagnostic procedure that may be used is a barium enema X-ray of the colon. After the colon is filled with barium, a chalky white solution, an X-ray is taken. The barium shows up white on the X-ray, providing a detailed picture of the colon and any signs of disease.

Medications Used to Treat Ulcerative Colitis

Currently, there is no medical cure for ulcerative colitis. However, effective medical treatment can suppress the inflammatory process. This accomplishes two important goals: It permits the colon to heal and it also relieves the symptoms of diarrhea, rectal bleeding, and abdominal pain. As such, the treatment of ulcerative colitis involves medications that decrease the abnormal inflammation in the colon lining and thereby control the symptoms.

Four major classes of medication are used today to treat ulcerative colitis:

- Aminosalicylates (5-ASA): This class of anti-inflammatory drugs includes sulfasalazine and oral formulations of mesalamine, such as Asacol,? Colazal,.? Dipentum,? or Pentasa,? and 5-ASA drugs also may be administered rectally (Canasa? or Rowasa? ). These medications typically are used to treat mild to moderate symptoms. Without inflammation, symptoms such as diarrhea, rectal bleeding, and abdominal pain can be diminished greatly. Aminosalicylates are effective in treating mild to moderate episodes of ulcerative colitis, and are also useful in preventing relapses of this disease.

- Corticosteroids: Prednisone and methylprednisolone are available orally and rectally. Corticosteroids nonspecifically suppress the immune system and are used to treat moderate to severely active ulcerative colitis. (By “nonspecifically,” we mean that these drugs do not target specific parts of the immune system that play a role in inflammation, but rather, that they suppress the entire immune response.) These drugs have significant short- and long-term side effects and should not be used as a maintenance medication. If you cannot come off steroids without suffering a relapse of your symptoms, your doctor may need to add some other medications to help manage your disease.

- Immune modifiers : Azathioprine (Imuran?), 6-MP (Purinethol?), and methotrexate. Immune modifiers, sometimes called immunomodulators , are used to help decrease corticosteroid dosage . Azathioprine and 6-MP have been useful in reducing or eliminating some patients’ dependence on corticosteroids. They also may be helpful in maintaining remission in selected refractory ulcerative colitis patients (that is, patients who do not respond to standard medications). However, these medications can take as long as three months before their beneficial effects begin to work.

- Antibiotics : metronidazole, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, others.

Complications of Ulcerative Colitis

Complications are by no means an inevitable or even a frequent consequence of ulcerative colitis, especially in appropriately treated patients. But they are sufficiently common and cover such a wide range of manifestations that it is important for patients and physicians to be acquainted with them. Early recognition often means more effective treatment.

Local complications of ulcerative colitis include profuse bleeding from deep ulcerations, perforation (rupture) of the bowel, or simply failure of the patient to respond appropriately to the usual medical treatments.

Another complication is severe abdominal distension. A mild degree of distention is common in individuals without any intestinal disease and is somewhat more common in people with ulcerative colitis. However, if the distention is severe or of sudden onset, and if it is associated with active colitis, fever, and constipation, your physician may suspect a serious complication of colitis, called toxic megacolon. Fortunately, this is a rare development. It is produced by severe inflammation of the entire thickness of the colon, with weakening and ballooning of its wall. The dilated colon is then at risk of rupturing. Treatment is aimed at controlling the inflammatory reaction and restoring losses of fluid, salts, and blood. If there is no rapid improvement, surgery may become necessary to avoid rupture of the bowel.

The Surgery For Treating Ulcerative Colitis

In one-quarter to one-third of patients with ulcerative colitis, medical therapy is not completely successful or complications arise. Under these circumstances, surgery may be considered. This operation involves the removal of the colon (colectomy). Unlike Crohn’s disease, which can recur after surgery, ulcerative colitis is “cured” once the colon is removed.

Depending on a number of factors,including the extent of the disease and the patient’s age and overall health, one of two surgical approaches may be recommended. The first involves the removal of the entire colon and rectum, with the creation of an ileostomy or external stoma (an opening on the abdomen through which wastes are emptied into a pouch, which is attached to the skin with adhesive). Today, many people are able to take advantage of new surgical techniques, which have been developed to offer another option. This procedure also calls for removal of the colon, but it avoids an ileostomy. By creating an internal pouch from the small bowel and attaching it to the anal sphincter muscle, the surgeon can preserve bowel integrity and eliminate the need for the patient to wear an external ostomy appliance.

Emotional Stress and Living With Ulcerative Colitis

Because body and mind are so closely interrelated, emotional stress can influence the course of ulcerative colitis — or, for that matter, any other chronic illness. Although people occasionally experience emotional problems before a flare-up of their disease, this does not imply that emotional stress causes the illness. There is no evidence to show that stress, anxiety, or tension is responsible for ulcerative colitis. No single personality type is more prone to develop ulcerative colitis than others, and no one “brings on” the disease by poor emotional control.

It is much more likely that the emotional distress that patients sometimes feel is a reaction to the symptoms of the disease itself. It is not surprising that some patients find it difficult to cope with a chronic illness. Such illnesses seem to pose a threat to their entire quality of life-their physical and emotional well-being, social functioning, and sense of self-esteem. People with ulcerative colitis should receive understanding and emotional support from their families and physicians. Although formal psychotherapy is generally not necessary, some patients are helped considerably by speaking with a therapist who is knowledgeable about IBD or about chronic illness in general.

Coping techniques for dealing with ulcerative colitis may take many forms. Attacks of diarrhea, pain, or gas may make people fearful of being in public places. In such a situation, some practical advance planning may help alleviate this fear. For instance, find out where the restrooms are in restaurants, shopping areas, theaters, and on public transportation ahead of time. Some people find it helps to carry along extra underclothing or toilet paper for particularly long trips. When venturing further afoot, always consult with your physician. Travel plans should include a large enough supply of your medication, its generic name in case you run out or lose it, and the name of physicians in the area you may be visiting.

People with ulcerative colitis accept the diagnosis with a wide range of emotions. Some people are angry for a time. Others feel a sense of relief at finally knowing what it is that has made them ill. While it certainly may help to come to terms with ulcerative colitis in a straightforward manner, since this approach may maximize your ability to be part of your health care team right from the start, everyone is different. Each person with the disease must adjust to living with ulcerative colitis in his or her own way. There should be no guilt, no self-reproaches, or blame placed on others as you come to grips with your illness. There are resources and information available, such as local support groups and IBD education seminars. No one with ulcerative colitis should ever feel alone. As you go about your daily life as normally as possible, try pursuing some of the same activities that you did before your diagnosis. Some days, you may not feel up to it. Other days, you will want to give it all you’ve got. Only you can decide what’s right for you. It will help to follow your physician’s instructions and maintain a positive outlook, and to take an active role in your care. That’s the basic (and best!) prescription.

While ulcerative colitis is a serious chronic disease, it is not considered a fatal illness. Most people with the illness may continue to lead useful and productive lives, even though they may be hospitalized from time to time, or need to take medications. In between flare-ups of the disease, many individuals feel well and may be relatively free of symptoms. But again, everyone is different, and it is up to you and your physician to find the treatment that works best for you.